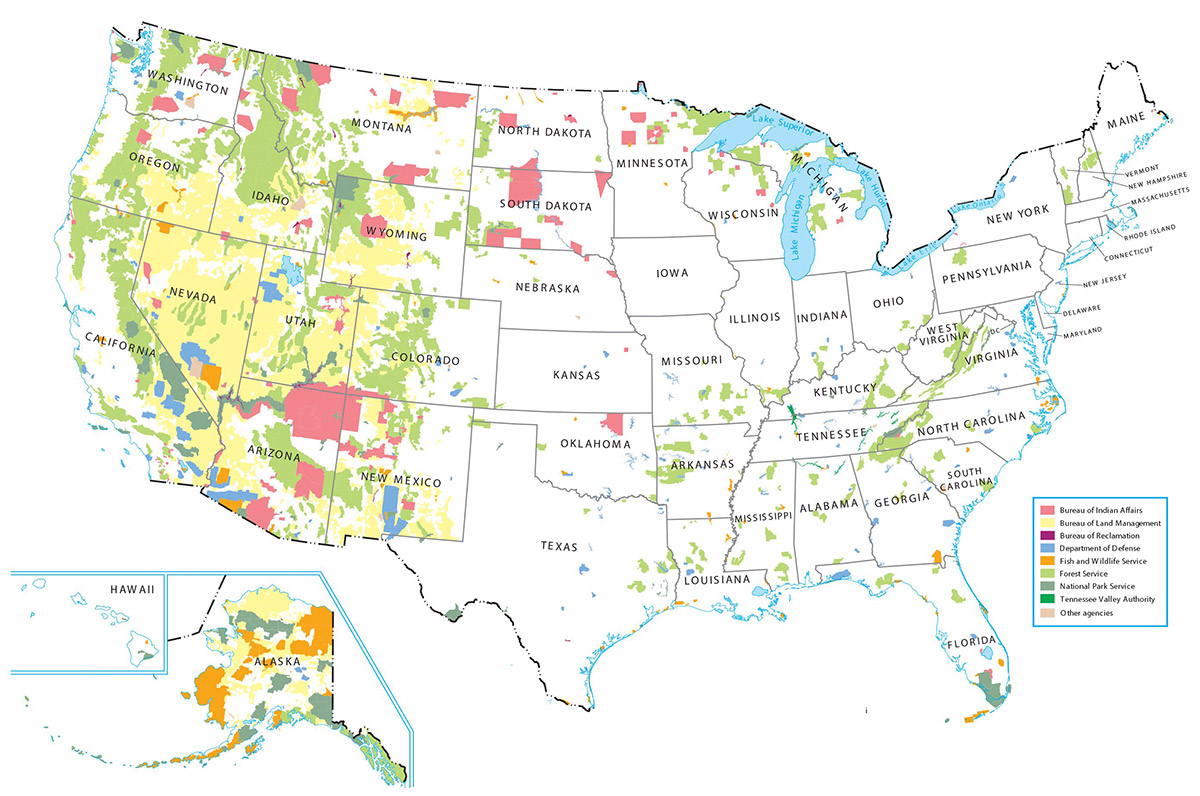

About one third of the United States is owned by us, the American people. For this extraordinary heritage—forests, grasslands, deserts, wetlands, glacier-topped mountains, canyons and rivers—we owe thanks.

First to the Indigenous peoples who have cared for these lands for millennia, and second to the architects of America’s public lands system, including Teddy Roosevelt, Ulysses Grant, Aldo Leopold, and many others, who sought to preserve outstanding scenery, reverse a near-extinction of buffalo, and “keep every cog and wheel.” They laid the foundation for a growing awareness that wildlife conservation requires, in many cases, lands free of resource extraction and development.

Our public lands nurture wildlife, sustain drinking water, offer sublime scenery, protect cultural and historic landmarks, and replenish our spirits, whether we go to hunt, fish, hike, camp, chase butterflies or simply watch the sun set. These lands also furnish timber, minerals, and livestock forage under the principle of sustained yield.

Public lands are crucial for invertebrate conservation

Without our federal public lands and associated conservation and management funding, many invertebrates—and the plants and other animals that depend on them—would be in trouble. A few examples show how wildland habitats and federal conservation efforts combine to make a real difference for invertebrates.

Western ridged mussel

Freshwater mussels live as long as humans, tirelessly filtering sediment and pollutants from rivers and streams. As larvae, most freshwater mussels attach to fish so they can reach new habitats while transforming into adults. Dams, water diversions, pollution, climate change and diminishing fish populations have caused western mussels to disappear from nearly a fifth of the watersheds they once inhabited. The Western ridged mussel is much diminished but strongholds remain on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service lands, and downstream areas that benefit from public lands management.

Fender’s blue butterfly

This inch-long butterfly was steadily disappearing as its prairie habitat was overtaken by agriculture and housing during the 1900s. However, the Fender’s prospects have markedly improved, due to a decades-long effort to restore its habitat on national wildlife refuges and BLM lands, coupled with federal research support and technical assistance for private land owners providing new habitat patches.

Western bumble bee

The once widespread western bumble bee has been lost from much of its former range, and now Forest Service lands in western states serve as important refuges. Like other bees, this bee helps perpetuate native flowering plants, which provide habitat and food for wildlife. Scientists believe domesticated bees conveyed a disease to wild populations, crashing the species. Numerous native plants and crops rely on bumble bees for pollination.

Changes in federal public land policy threaten wildlife

For more than 100 years, public lands have been held in trust for the American people and Americans overwhelmingly support protecting public lands. Nonetheless, new and proposed federal policies and budgets threaten the habitats and programs that support invertebrates and other wildlife on public land.

For example, the recently enacted One Beautiful Big Bill Act will dramatically increase logging on federal lands and mandates quarterly oil and gas leasing on 200 million acres of public lands. The bill also would make fossil fuel extraction cheaper by re-establishing non-competitive leasing and reducing royalty rates.

Other threats are contained in the 2026 appropriations process (which has begun), and in various orders, rules and memos. These include, but are not limited to:

- Cutting federal agency staff and funding: The president’s 2026 budget proposes cutting more than $1.7 billion from the four main land management agencies, targeting conservation, operations, and ecological research funding. These funds are a tiny portion of the overall federal budget, but the cuts would have a big impact on National Parks operations, as well as conservation and science programs that help sustain plants and wildlife. These will cement and potentially increase staffing cuts since January that reach 40% or more on some units of land management agencies.

- Severing endangered wildlife from their habitat: A proposed rule change would severely weaken habitat protections for endangered species. Additional rule changes for this landmark law are reportedly under review.

- Increasing logging in national forests: An executive order signed March 1, 2025 establishes an “emergency” that mandates fast-tracked logging on huge areas of National Forest System lands, including some designated wilderness, roadless areas, and critical habitat for endangered species. The order and a subsequent memo allows the U.S. Forest Service to bypass standard environmental and endangered species reviews.

- Opening roadless areas to development: The administration plans to rescind the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, which protects 58 million acres of national forests from road construction, logging, mining, and invasive species. At special risk are the Tongass and Chugach National Forests in Alaska, known locally as the “salmon forests” because they supply 48 million salmon annually to the commercial fishing industry. Their roadless watersheds contain thousands of miles of clean, cold rivers full of the aquatic invertebrates salmon require.

- Fast-tracking mining: A Department of Interior memo signed April 23, 2025 seeks to accelerate mining on federal lands by setting aside requirements under bedrock environmental laws that have been in place since the 1970s, and slashing or eliminating opportunities for public comment that have been routine for decades.

These changes would hurt invertebrates, other wildlife, and all of us who depend on natural resources through:

- Direct loss of habitat

- Hastening the loss of forest canopy, exacerbating warming and drying of watersheds

- Causing erosion and pollutants to enter streams and rivers

- Gutting scientific research critical for advancing our understanding of ecosystems, and

- Removing tools that would help reduce the risk of wildfire

You can speak up for public lands

The Xerces Society stands for public lands; they are critical for invertebrate conservation and the perpetuation of plants and animals across America. Taken together, proposed new policies would waive existing legal protections for public lands, setting the stage for irreversible development, mining and logging while wildlife pay the price.

You can help! A massive public outcry helped stop a recent attempt to sell off public lands. Now your elected officials need to hear your concern about these less-publicized changes in store for public lands.

Call your senators and representatives using the U.S. Capitol switchboard at (202) 224-3121. Tell them you oppose cuts to federal conservation spending proposed in the 2026 budget, and oppose massive increases in extractive activities on our public lands, and weakening of the nation’s bedrock environmental laws. And remind them that public lands must stay in public hands.