Last year, the Xerces Society partnered with the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to launch the Cascade-Siskiyou Butterfly Monitoring Network. Though the 2020 field season is facing uncertainty, there are still ways for you to get involved with butterfly research where you live.

Sitting in my living room looking out at all of the spring flowers in bloom, it’s hard not to get excited for warmer months ahead. This time of year usually means preparing for the upcoming field season, but like many of you, I’m not sure what the next few months will hold. Millions of people are practicing physical distancing to protect the lives of themselves and others as the coronavirus sweeps across the world.

Because of the current situation, it may seem like a strange time to talk about butterfly surveys and community science initiatives. But perhaps, now more than ever, we need things to look forward to. For me, butterfly season is a bright light on the horizon.

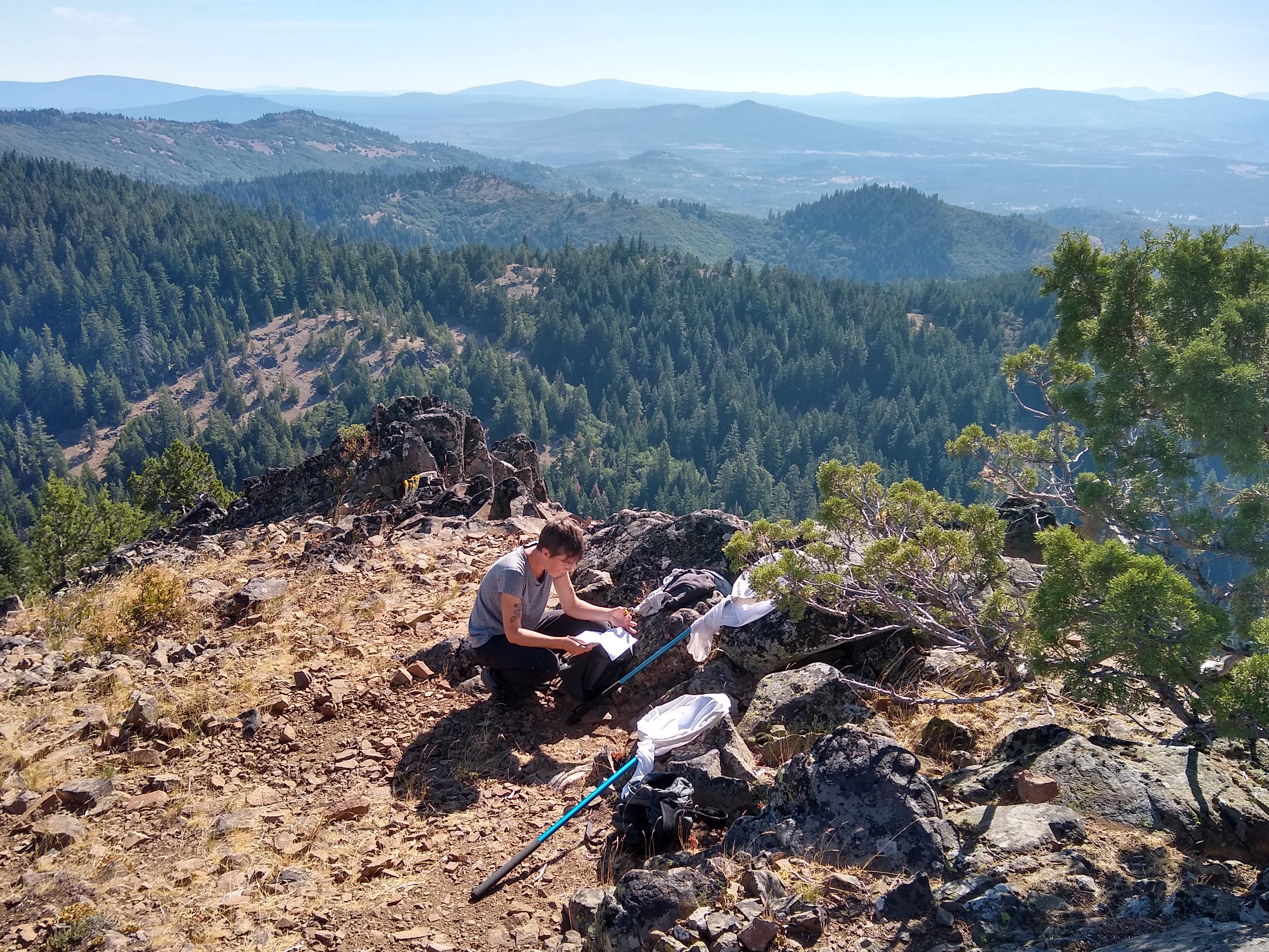

Xerces and Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument staff and volunteers conduct butterfly surveys in the National Monument during summer 2019. (Photo: Xerces Society / Candace Fallon)

As it turns out, butterflies are popular targets for community science initiatives, and they have been the focus of monitoring efforts for decades. They are relatively easy to observe and identify, are generally well-described taxonomically, and can often be identified using readily available regional field guides.

Butterflies are also important indicators of ecosystem health—since changes in their populations may reflect the effects of habitat alteration, shifting climate, and changes in plant communities. Because insect populations naturally fluctuate from year to year, long-term monitoring is important for providing an accurate picture of species distribution and population trends. This type of monitoring also provides land managers with a tool to identify future research needs and inform adaptive management. Furthermore, it helps us to prioritize conservation actions for at-risk species and habitats, and effectively prevent the decline of other species.

The author holds a western pine elfin (Callophrys eryphon), photographed in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in summer 2019. (Photo: Xerces Society / Candace Fallon)

Modified Pollard walks, first officially described in 1977, are one of the most commonly-used methods for long-term monitoring butterfly populations. These are fixed-route transects at established sites that are surveyed on a regular basis year after year. Ideally, surveys occur weekly during good weather conditions while butterflies are active (roughly April through September, depending on location).

Transects can be of different lengths, but many programs utilize a fixed 1000 meter transect length that is broken up into distinct segments to reflect different habitat types. Surveyors slowly walk the transect, recording all butterflies seen within an invisible 5 meter box that stretches out in front of them. Species identifications are made visually, using binoculars when needed, or briefly catching individuals with nets to confirm identification and take photos. Butterflies are then released, unharmed.

Pollard walk monitoring programs have been established all over the world. They are especially popular because they require relatively low input and effort compared to other survey types, allow for replication (a key part of the scientific method), and provide information on presence-absence and relative abundance—valuable data for land managers who are interested in the conservation of butterflies and their habitat.

The author conducts a butterfly survey in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. (Photo: Xerces Society / Emma Pelton)

In the US, these programs and many other types of butterfly monitoring programs are part of a much larger network called the North American Butterfly Monitoring Network. This network was established in 2012 with the goal of developing shared approaches to data management, visualization, and analytical tools designed to handle the tens of thousands of observations that are made each year, often using different survey protocols and data management systems.

Last year, the Xerces Society partnered with the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to launch a new long-term monitoring program, the Cascade-Siskiyou Butterfly Monitoring Network (CSBMN). Straddling the Oregon-California border, the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is a biodiversity hotspot where the Klamath, Siskiyou, and Cascade Mountain Ranges come together to form unusual plant communities and species assemblages. Due to this complexity, butterfly diversity is also exceptionally high. However, no comprehensive monitoring programs for butterflies had previously been established in the area.

Last year, the Xerces Society partnered with the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to launch a new long-term monitoring program, the Cascade-Siskiyou Butterfly Monitoring Network (CSBMN). Straddling the Oregon-California border, the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is a biodiversity hotspot where the Klamath, Siskiyou, and Cascade Mountain Ranges come together to form unusual plant communities and species assemblages. Due to this complexity, butterfly diversity is also exceptionally high. However, no comprehensive monitoring programs for butterflies had previously been established in the area.

A Clodius parnassian butterfly (Parnassius clodius), documented for a survey in summer 2019. No butterflies were harmed in the making of this photo; the surveyors used a standard technique to hold the wings safely. (Photo: Xerces Society / Candace Fallon)

The CSBMN, which is focused on the Monument but also includes other private and public lands in the area, was officially launched as a pilot project in May 2019. Our goals during this first year included setting up the initial transects, developing site-specific species lists, and training and engaging local volunteers to adopt and monitor sites in 2019 and beyond. To date, seventeen routes have been established on the Monument and two adjoining properties. Based on data submitted by surveyors in 2019, nearly 2,100 butterflies were counted on 14 of these transects. More data are expected to be submitted in the coming months, but already this represents approximately 69% (76 species) of the known butterfly fauna on the Monument.

Since 2019 was a pilot year, we had anticipated fully rolling out the new monitoring program in 2020. As of right now, the first training session of the year is scheduled for the end of May, led by partners at the Vesper Meadow Education Program. However, evolving physical distancing guidelines and state and federal restrictions may result in a cancellation or postponement of this training. If you live in the area and are interested in updates to this program, I recommend reaching out to project coordinators. And if you live elsewhere but want to get more involved in butterfly monitoring programs, definitely check out the North America Butterfly Monitoring Network, which lists dozens of programs around the country.

There are many great butterfly guides out there, including Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest by Robert Michael Pyle and Caitlin C. LaBar (pictured). (Photo: Xerces Society / Rachel Dunham)

In the meantime, it couldn’t hurt to brush up on your species ID skills. Although libraries are closed, many bookstores are still shipping (you could find a butterfly guide for your area!), and there’s a plethora of resources online. Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) is a great place to get started, as is iNaturalist. Consider strengthening your plant identification skills at the same time, so you can better recognize important host and nectar plants that grow in your area.

If you have a yard or garden or safe access to a local natural area, take your camera and a field guide (or even just your smart phone), and get to know the species that are starting to bloom and take flight. You can even post your observations to BAMONA and iNaturalist, effectively contributing to other community science programs while you learn new skills for other ones. If you have an outlet for gardening, plant a few native species for your local butterflies. Do some research to see what host plants are needed by the species in your area. Encourage kids to draw pictures of butterflies they’ve seen or would like to see one day, maybe even on their known host plant or a preferred nectar plant.

Bottom line: There is no shortage of ways to engage in butterfly conservation, even if we need to get a little more creative these days.

Further Reading

Check out the Xerces Classroom Series video, Beautiful Butterflies, which was filmed on-site at the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument.

Learn more about the Xerces Society’s Endangered Species Conservation Program.

Check out the rest of our Earth Week content!