Select updates from our team of restoration ecologists, entomologists, plant ecologists, and researchers.

The Xerces Society manages the largest pollinator conservation program in the world. We work with people from all walks of life to create habitat for bees, butterflies, and other beneficial insects—and hundreds of thousands of acres of flower-rich habitat have been planted. We also offer certifications: Bee Better Certified for farmers and food companies who are committed to supporting pollinator conservation in agricultural lands, and Bee City USA and Bee Campus USA for cities and colleges dedicated to making their community safer for pollinators.

With staff based in more than a dozen states, and offering a diverse array of expertise, it can be challenging to summarize the impactful work being done. We compile updates from pollinator team members into regular digests. In this edition, Hannah Mullally describes a project to create a pollinator habitat demonstration site in the unique conditions of northern Maine, Karin Jokela shares her experience and suggestions for designing conservation seed mixes in Minnesota, and Anna Murray gives a glimpse into habitat planning and monitoring in California.

Pollinator Habitat Demonstration Site in Northern Maine

Hannah Mullally

In 2020, I met with Central Aroostook Soil and Water Conservation District, Presque Isle NRCS field office, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to plan the creation of a 7-acre pollinator demonstration area near Presque Isle, Maine. The objectives of this demonstration area are to test site preparation methods in the field, test habitat management techniques, provide public education about pollinator habitat establishment and management, and serve as a site for long-term insect and vegetation surveys. Northern Maine’s climate, soils and vegetation are unique from the rest of Maine making this an important project to inform pollinator habitat creation here in the future.

Because this is a demonstration site, the habitat plan I created outlined different site preparation methods to be applied in sections of the area, including herbicide, tillage and smother crop, and smothering with black plastic. A separate section will demonstrate inadequate site preparation of only one tillage passage to illustrate the need for thorough, season-long preparation. I also created a timeline for site preparation and seeding, management techniques, and a seed mix which includes milkweed suitable for the climate. A section of the demonstration area will not be seeded and the existing vegetation will be managed to maintain early successional habitat. Each of the different treatment areas are clearly defined by mowed boundary strips.

Public field days will be help to introduce landowners to site preparation methods, native plants, the needs of at-risk species including the monarch, and appropriate management. Partners and I will conduct annual surveys on the site to monitor changes in pollinator and vegetation presence.

Demonstration site at Presque Isle, Maine, in October 2020. The mowed strip is a boundary separating sections with different treatments. (Photo: Xerces Society / Hannah Mullally.)

The Science and Art of Pollinator Seed Mix Design

Karin Jokela

In the Midwest, most large-scale native pollinator habitat plantings are created with seed mixes. It is understood that plant diversity is a requirement for pollinators and the foundation of ecological resilience, but it can be a complicated and consequential challenge to select the best mix for any given site. After all, what you plant when you start a project determines the results for years to come.

The majority of my work during this travel-restricted year has centered around designing and reviewing mixes for farmers and agency staff, as well as training conservation professionals on how to build high-quality native seed mixes that serve bees and monarch butterflies, replicate natural plant associations, establish readily, conform to certain conservation practice standards, AND fit within budget constraints. It takes a lot of familiarity with native flora, experience with specialized design tools like seed calculators, and awareness of the commercial availability of various species in our region. No doubt, a certain bent for artistic creativity can also be helpful when crafting the perfect mix.

In the past year, I’ve led seven seed mix design and evaluation training events for conservation staff from city, county, state, and federal agencies as well as private consultants and individuals, and I think I’m only scratching the surface of the demand here in Minnesota. Readers of this digest might also be interested in how to evaluate a mix that purportedly benefits pollinators. Here’s a list of questions I ask myself when reviewing a mix for the tallgrass prairie systems common in the Midwest. In most cases, there isn’t a “correct” answer to each of these questions, but thinking through these considerations can help you explore which elements in a mix may need to be adjusted prior to purchase:

- How many species are in the mix?

- Are the species regionally appropriate?

- Are the species adapted to the soil moisture conditions on site?

- Are the species adapted to sun conditions on site?

- Are there at least three (ideally, more!) wildflower species blooming in each part of the growing season (early, mid, and late?)

- Are there native sedge and grass species, including some bunchgrasses?

- Are butterfly host plants included (e.g., milkweeds for monarch butterflies)?

- Are annuals, biennials, and short- and long-lived perennials included?

- Is there a wide diversity of native plants from different plant families (e.g., asters, mints, milkweeds, legumes, roses, etc.)?

- Are all the “functional groups” represented (e.g., warm-season grasses, cool-season grasses, sedges or rushes, legume and non-legume wildflowers)?

- Are there any species dominating the mix (i.e., species that have an unusually high seeding rate that could outcompete others)?

- What is the ratio of wildflowers to grasses (based on seeds/square foot)?

- What is the overall seeding rate?

- Does the cost match my budget?

- Are the species in the mix available to buy? If not, what substitute species would be appropriate?

Hopefully this list of considerations will be useful as a way to visualize how a particular seed mix may perform, and whether your mix will help you achieve your conservation goals. There’s inherent optimism in creating mixes with affection and intention, knowing that once established, your habitat will serve as a powerful nature-based climate and biodiversity solution. Enjoy the process!

Pollinators need an abundance of diverse flowers blooming throughout the growing season. Native seed mixes like the one pictured here will offer important host plants for bees and butterflies once established. (Photo: Justin Meissen, Tallgrass Prairie Center [CC BY-SA 2.0].)

Expanding On-Farm Habitat Creation Projects to Include Monitoring

Anna Murray

Since joining Xerces in May 2020, my work has primarily focused on ensuring the continuation of pollinator habitat establishment on farms that form part of the General Mills supply chain in the western United States. In addition to working with almond, tree fruit, and vegetable row growers to plant pollinator and beneficial insect habitats, I am adding a focus of detailed monitoring of plant health and phenology (the timing of seasonal events) to our work.

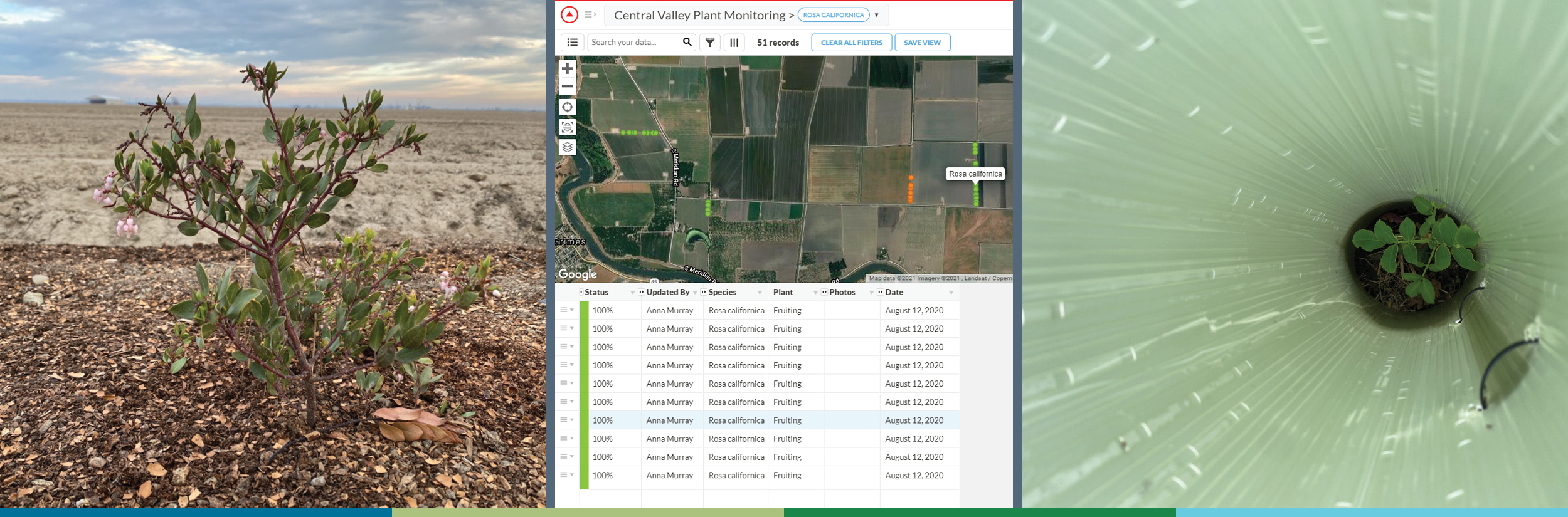

Using an online platform called Fulcrum, I have customized field-collection forms to capture media-rich, geo-located information on the habitats that have been planted throughout the supply chain and Bee Better Certified farms. We hope to capture this information to 1) create a system for extensive photo-monitoring and storytelling; 2) create a large set of data to help us understand plant survival, adaptability, and phenological variation, and—time permitting—invertebrate use of these large-scale projects; and 3) maintain connections with our grower partners and encourage investment in the continuing maintenance of their habitat plantings.

A glimpse at the real and virtual world of habitat planning, establishment, and monitoring: (from left) manzanita planted in a hedgerow in Colusa County; computer screenshot of Fulcrum monitoring data; looking down at elderberry growing within the protection of a tube shelter. (Photos: Xerces Society / Anna Murray.)

Further Reading

Learn more about the Xerces Society’s Pollinator Conservation Program.

Find out how you can help Bring Back the Pollinators.